The court is unable to make an order in relation to the division of property unless it is satisfied that an order altering the interests of the parties in their property is just and equitable and that the order proposed to be made, is just and equitable: section 79(2) Family Law Act 1975 and section 90SM(3) Family Law Act 1975.

What does just and equitable mean?

The words ‘just and equitable’ have been described by Justice Dawson in Mallet & Mallet as being the “overriding requirement” to determine whether it is just and equitable to make AN order at all and what THE order should be, if one is made. In determining whether the order is just and equitable, the court must consider the justice and equity of the outcome, i.e. the actual order itself, not just the underlying percentage (%) distribution of the assets: Russell & Russell [1999] FamCA 1875 and JEL v DDF [2000] FamCA 1353.

The main purpose of section 79(2) is to ensure that the Court’s power is not exercised in an unprincipled fashion. There must be a principled reason to interfere with the existing legal and equitable interests of the parties. In other words, the Court must not alter the property rights of parties unless justice requires it to do so and if the court decides it is just and equitable to make an order, the court must then be satisfied that the alteration of property interests goes no further than the justice of the matter demands.

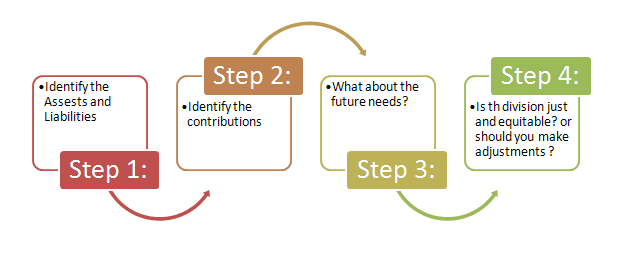

What are the four steps?

The four steps considered by the Court in determining what orders it makes, as set out in Hickey, are

- identify the value of the property, liabilities and financial resources of the parties at the date of the hearing;

- identify and assess the contributions of the parties and determine the contribution based entitlements of the parties as a percentage of the net value of the property pool;

- identify and assess the ‘future needs’ factors under section 79(4) and 75(2) of the Family Law Act so far as they are relevant and determine any adjustment necessary (if any).

- consider the effect of those findings and determination as to what order is just and equitable in all the circumstances of the case.

In property disputes, the court’s decision making process involves a broad and independent exercise of discretion, having regard to these four steps, which turns on the facts of each individual matter: Russell & Russell [1999] FamCA 1875.

The 4-step approach is not a legislatively mandated approach but the preferred approach that merely illuminates the pathway to the ultimate result culminating in a consideration of whether the proposed orders are just and equitable.

In Mallett & Mallett (1984) 156 CLR 605 and various future cases ending in Hickey & Hickey [2003] FamCA 395, the Court has discussed that the just and equitable requirement is generally considered to be the identifiable fourth step. This is because it will be sufficient in most cases to have regard to the overall justice and equity of the orders after determination of the asset pool, consideration of the contributions of the parties and assessment of relevant future needs (s75(2)) factors.

However, it has been discussed in more recent cases such as Martin & Newton [2011] FamCAFC 233 and Bevan & Bevan [2013] FamCAFC 116 that there is no requirement that the justice and equity of the order as prescribed under section 79(2) must only be considered at the 4th and last stage. These cases set out that the requirement to make an order that is just and equitable permeates the entire decision making process and it is not impermissible to consider it at an earlier point if a case requires it.

Furthermore, in the recent case of Rigby & Kingston (No. 4) [2021] FamCA 501, has clarified that the requirement set out in the cases of Omancini and Stanford to first identify the legal and equitable interests of the parties does not require that a valuation of the property of the parties be obtained prior to a determination of whether it is just and equitable to make an order, and whether a valuation is required will depend on the circumstances of the case.

The effect of Stanford

The case of Stanford v Stanford [2012[ HCA 52 provided an opportunity for the High Court to provide its views on the proper approach to an application for property adjustment under section 79 of the Family Law Act.

In Stanford, the High Court stated that in any application, the Court must first consider whether it is just and equitable to make AN order, rather than simply considering whether the order is just and equitable as a ‘fourth step’. The case did not approve/disprove the four-step process but served to refocus attention on the obligation of the Court not to make an order adjusting property interests unless it was just and equitable to do so and, in this regard, there must be a “principled reason for interfering with the existing legal and equitable interests of the parties to the Marriage”.

In Watson & Ling (2013) Justice Murphy confirmed that “As Stanford makes plain (especially at [39]) the breakdown of a marriage (or de facto relationship as defined in the Act) does not bring as an automatic consequence an alteration of existing legal and equitable interests. Just as, if an order is to be made, equality is neither to be assumed nor is a starting point (Mallett v Mallet), so too, the making of an order at all is not to be assumed.”

Accordingly, the requirement to consider whether an order is just and equitable is and may be considered as a first step, but as the more recent cases set out, the requirement to do justice and equity is not a threshold issue but rather one permeating the entire process.

How is the just and equitable requirement (as a first step) satisfied?

It is clear from Stanford that in many cases the just and equitable requirement, as a first step, is satisfied because once the parties are no longer living together, there will no longer be common use of the property and the express or implied assumptions previously underpinning the parties’ property arrangements will have been brought to an end. This is the situation in the vast majority of cases. The question of whether it is just and equitable to alter the existing property interests in that particular case will be readily answered where both parties are seeking orders which alter their respective property interests. Whether it is just and equitable to make an order is more difficult to answer where one party argues that it is not just and equitable to make any order altering the interests of the parties in their property.

The Big Ticket Cases dealing with section 79(2) – where the Court held it was not just and equitable to make any order

Bevan & Bevan – 18 year separation and representations made by Husband that wife could keep assets

In Bevan & Bevan [2013] FamCAFC 116 the primary issue in the appeal was whether the trial judge erred in determining that it was just and equitable to alter the existing property interests of the parties when the parties separated and largely lived apart for 18 years and the husband had told the wife she could retain certain assets. The Trial Judge had held that the Husband induced the Wife by his conduct that he did not wish to make a claim on any property in Australia and she was entitled to use that property as she wished for her benefit and that of her boys. Despite this, the Trial Judge ordered that the property pool be divided 60/40 in favour of the Wife. On appeal the Wife argued that the Trial Judge did not look at the justice and equity of the circumstances for the parties, namely that the wife would be without a home and unlikely to be able to obtain another where the husband had accommodation that was assured and he had used his income post separation as he chose. The trial judge said that the husband’s representations had no direct bearing upon what he was entitled to receive and in effect the only way the Trial Judge took the Husband’s representations into account was as a shield to the addback argument by the Husband which ultimately, he did not run. The Wife argued that the finding about the representations by the Husband that the Australian property was hers should have been taken into account to ameliorate the level of contributions by the Husband.

On the rehearing of the matter, the Court held that the Trial Judge was in error by failing to take into account the parties representations during the marriage and post separation as a threshold question before considering the contributions of the parties under section 79(4). The representation of the Husband was a material factor that should have been taken into account in determining the threshold question of whether it was just and equitable to make an order. The appeal was allowed. Matter was remitted for rehearing.

On rehearing, the Full Court found that given the extent of the husband’s representations including all the circumstances in which they were made and the husband’s substantial delay in commencing proceedings (16 years), it would not be just & equitable to make any order interfering with existing interests in property. The Husband’s application for property adjustment was dismissed.

Redman & Redman – parties sought property settlement orders while relationship intact

In Redman & Redman [2013] FamCAFC 183 the Full Court looked at the just and equitable requirement as a first step. The husband and the wife made an application for consent orders to be made. The sole purpose of the orders sought was to transfer the family home in an intact marriage from the name of the husband to the names of both himself and his wife and to employ the Family Law Act 1975 to achieve this so that stamp duty (very minute in the circumstances) could be avoided. The Registrar declined to make the order. When the decision was appealed, the Court indicated that it does have power under section 79 to make orders in circumstances where the parties marriage is ‘intact’ and had not broken down (Stanford 117 – 118). However, as Stanford says, the court must have a principled reason for interfering with the existing legal and equitable interests of the parties to the marriage. The Court held that there was no reason apparent on the facts and the appeal was dismissed.

Fielding & Nichol – 12 year relationship where court determined not just and equitable to make any order

In Fielding & Nichol [2014] FCWA 77, the Court found that it was not just and equitable to make any orders altering the interests of the parties in their property in circumstances where the parties had kept their property and finances separate throughout the duration of the relationship and neither provided for the other in their wills. Furthermore, the assets which were kept entirely separate continued to exist in precisely the same form in which they were held at the commencement of cohabitation.

The Court held there was an absence of evidence that the de facto husband refrained from accumulating other assets or changed his position as a result of having the benefit of using the de facto wife’s home during their relationship. The de facto Husband argued that he had made a significant contribution to the property owned by the de facto Wife in which they resided during the relationship. In response to that argument, the Court held that the extent of the work done by him around the de facto wife’s property was not such as to lead to a conclusion that it would be just and equitable to adjust the existing property interests of the parties, especially given the de facto husband and for a time his son lived in the matrimonial home rent free. It was further noted that whilst the assets of the de facto wife exceeded that of the Husband, both had access to an asset which could be realised to meet their expenses that could not be met from their current income.

Chancellor & Mccoy – 27 year de facto relationship where court determined not just and equitable to make any order

In Chancellor & Mccoy [2016] FCCA 53, the circumstances were that the parties conducted their financial affairs separately and there was no intermingling of finances (Ms Chancellor’s payments to Ms Mccoy while living at her property were considered financial assistance not intermingling). They did not have joint bank accounts. Each party was free to use their money as they chose. Each party retained property in their own name. They were responsible for their own debts. They were not involved in each others financial decision making or made aware of the others financial situation. Neither made significant improvements to the value of the other’s property (there was no evidence that the financial and non-financial contributions of Ms Chancellor to Ms Mccoy’s properties when assisting in renovating improved the value of these properties). Neither party made provision for the other through their will or life insurance. At the end of the relationship, Ms Chancellor was left with significant assets accumulated by her during the relationship, including two houses, several motor vehicles and superannuation. Ms Mccoy had retired by the time of trial and Ms Chancellor was still in employment and had the capacity to accumulate more assets and contribute to her superannuation fund.

The court decided in this case that the just and equitable outcome was that each party be allowed to keep the assets they had, without any adjustment.

This decision was appealed on numerous grounds including that the decision was manifestly outside the range of the reasonable ambit of discretion. All appeals were dismissed.

Tran & Kingsley – court determined not just and equitable to make an order due to lack of disclosure by the wife

In Trang & Kingsley [2017] FamCAFC 120, the Wife failed to account for her use of $250,000 pre and post separation. The Court noted further concerns about her disclosure of the identity and value of property interests she had overseas. Trial Judge was therefore unable to identify and value the property interests of the parties save for the Wife’s super. The Court held it was not just and equitable to alter the interests of the Husband in favour of the Wife. Central to the Court’s determination was the fact that findings were made as to the wife’s failure to disclose her financial circumstances. The Wife appealed and the findings about her credit on appeal were not challenged. The appeal was dismissed.

Grady & Chilcott – no order just and equitable after 8 year de facto relationship

In Grady & Chilcott (2020) FamCAFC 143, the Court held that it was not just and equitable to make an order adjusting the interests of the husband in favour of the wife. The circumstances were that the parties were in a de facto relationship from 2005 to 2013. When they commenced cohabitation, the de facto husband owned 4 properties and ran a successful business. The Wife made no financial contributions to the acquisition of any of the properties not did she contribute to the parties living expenses other than for groceries.

During the relationship, the husband purchased another property with his funds which the wife made no financial contribution to directly or indirectly. The Wife was in paid employment during the relationship and was able to save her whole income which allowed her to purchase properties in another country where her family lived rent free. The Wife stole $141,000 from the husband and was charged with offence relating to this and she was ordered to pay compensation which she had never paid. The Husband liked to gamble and would borrow money from the wife which was ultimately repaid. The parties kept separate finances during the relationship. By the time of the trial the husband’s business had closed down and he had ceased working. The Wife had ceased work and her employment terminated due to criminal charges.

At first instance and upheld on appeal, the court found that whilst the Wife purchased groceries and lent the husband money when they went out (later repaid) the husband made the overwhelming financial contributions to the relationship.

Rigby & Kingston – no order just and equitable after 23 year marriage and 2 children

In Rigby & Kingston (No. 4) [2021] FamCA 501, the property pool was somewhere at least $7M. The Husband argued that various interests of the Wife in the Kingston group, which he said could be worth up to $100M, were part of the property pool. The Wife conceded that if her interests in the Kingston group equated to a proprietary one, her one third interest could be valued at up to $50M. The Court held that the interests of the wife in the trusts and entities, created for the purpose of distributing to her income and assets from her Father’s will, were not property as she had no absolute right to income/assets of the Trust.

Separately, the Wife argued that it was not just and equitable to alter the interests of the parties. The circumstances were that the parties were in a relationship/married for 23 years and had 2 adult children. The parties entered into a prenuptial agreement with respect to how their property interests ought to be arranged and that each party would retain their own separate property. That prenuptial agreement was not determinative as it was not a prenuptial agreement under the Family Law Act. During the relationship, the parties never shared bank accounts or joint assets. The parties maintained ledgers of their expenditure.

The financial contributions of the Wife greatly exceeded the Husband. The wife received substantial distributions from the trusts controlled and established by her father throughout the marriage as well as inheritances. The parties lived in a property acquired by the wife, funded by the wife, and the Husband made no financial contribution to those properties which she controlled exclusively. The Husband worked on those properties but was paid. The Husband was out of work for substantial periods of time and suffered alcoholism and obesity in the latter half of the marriage. Despite the Husband having more availability, the Husband’s non-financial contributions did not exceed that of the Wife who remained primary carer and homemaker for the children. The Husband conceded that in order to marry the wife her father required that he sign a BFA he had prepared as he wanted to protect his wealth from any of the spouse partners of his children her his will and he established a testamentary trust for this purpose.

The majority of the Wife’s wealth was derived from her inheritances and distributions from the Kingston group and a salary paid to her.

From 2007, the Wife gained advantage by distributing income to the husband and paying less tax which advantaged the husband as otherwise he would have been unable to pay living expenses.

The court held that the only reason why it would be just and equitable to alter the interests of the parties would be because of section 75(2) factors, that being a clear disparity in the parties financial resources as the Wife owned substantial property and the Husband owned virtually nothing. The wife’s income also greatly exceeded the Husband. The Court held that to make an order solely on the ground of future needs factors would be to do what the High Court cautioned against in Stanford – to make an order only because of s79(4) factors (in this case – future needs). The Court held that if the Husband is unable to maintain himself then he has a right to claim spousal maintenance. The Court held that it was not just and equitable to make an order altering the interests of the parties in their property.

Are you unsure as to what order is just and equitable in your case?

If you have recently separated we strongly recommend that you get in contact with one of our experienced family lawyers as soon as possible, for a confidential reduced rate consultation, at which time we can provide you advice in relation to your entitlements and what orders are just and equitable in your case.

Contact us on 3465 9332 to arrange your reduced rate initial consultation today.